A Guide to Malolactic Fermentation

Malolactic Fermentation, also known as Secondary Fermentation or “Malo”, is the process in which Malic Acid in the wine converts to Lactic Acid.

What is Malolactic Fermentation?

As stated above, it is the process in which Malic Acid in the wine converts to Lactic Acid. The primary role of Malolactic Fermentation is to deacidify the wine which affects the sensory aspects of wine, making the mouthfeel smoother and it adds complexity to the flavor and aroma of the wine. The deacidification of the wine happens by converting the harsh diprotic malic acid into the softer monoprotic lactic acid. Nearly all red wines go through Malo while only a few whites, like Chardonnay and Viognier, do. One way to recognize if a wine has gone through Malo is if it has a creamy, buttery mid-palate texture. The buttery flavor comes from diacetyl, a by-product of the reaction.

What is Diacetyl?

Diacetyl is a flavor metabolite produced by lactic acid bacteria known as Oenococcus Oeni. Oenococcus Oeni is the main bacteria responsible for conducting Malo, due to its ability to survive the harsh conditions of wine. It is responsible for the production of the sensory aspects noted above. Malo can happen naturally, though often inoculated with the bacteria culture to jumpstart the process.

When does Malo take place?

Malolactic Fermentation can happen in two different ways, during primary fermentation or after. Amid fermentation, it is Co-Inoculation. After fermentation, it is Post-Fermentation Inoculation. Inoculation that takes place after alcoholic fermentation is the most common practice. When you add bacteria cultures like MBR31 after fermentation is complete, it jumpstarts the Malo process. Co-inoculation takes place at the start of alcoholic fermentation, which allows winemakers to focus on other things such as the improvement of flavor development.

What are the signs that Malo is in progress, and how do I know if it is finished?

The best way to identify malo in progress is bubbles! The malolactic activity can be detected by the presence of tiny carbon-dioxide bubbles. When the bubbles stop, Malolactic Fermentation is complete. This can take anywhere between one and three months.

What are the benefits of each method?

Firstly, the benefits of post-fermentation inoculation include better control of the start time duration of Malo. Lessened biogenic amine production leaves the wine unprotected by sulfite for a limited amount of time. This allows less potential for spoilage by other organisms. It reduces the incidence of excessive volatile acidity and enhances flavor profiles and complexity. The benefits of co-inoculation include lower levels of the inhibitory alcohol that are present at the start of Malo, and no need to apply external heating to the ferment due to the heat generated by the yeast fermentation. This results in faster completion of Malo. This means the wine can have sulfite added earlier and reduces the potential for the growth of spoilage organisms. Finally, a bonus is that bacteria added at the start of the yeast fermentation encounter a nutrient-rich environment.

Need assistance with your winemaking process?

Musto Wine Grape Company is here to help. We offer a wide variety of products and services to help you at any stage in your winemaking journey. Email winemaker@juicegrape.com or call us at (877) 812-1137 to speak with someone who can assist you.

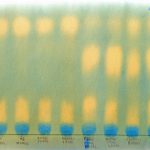

How to do paper chromatography

Paper chroma-whata??

Paper chromatography: the way that home winemakers (and some commercial winemakers) check to see if their wines have completed malolactic fermentation or if they are still in the process of it. This is the time of year that winemakers are staying up on at what point their wine is at in the process of malolactic fermentation, because it will dictate when they can add potassium metabisulfite for the first time to their finished wine.

Why is it important?

Some wines should go through MLF for stylistic and stability reasons, whereas others should not.

How do I do it?

You’ll need to get a paper chromatography kit. This includes 3 acid standards (malic, lactic, tartaric), the solvent solution, chromatography paper, capillary tubes, and a plastic jar.

How accurate is it?

That’s the thing – it’s more qualitative than quantitative. Maybe it will show that there is still malic acid present, but that doesn’t mean it tells you how much is present, how long it’s been at this point, or if it’s even still decreasing anymore. It is qualitative in the sense that it shows: yes, acid X is present, or no, acid X is not present. If you’re searching for a more exact number or reference point you can send your samples in to a lab – if you’re looking to get an overall picture of whether or not your wine has any malic acid or lactic acid present, then using paper chromatography is the way to go.

What does this stuff look like?

How do I do it?

- Collect your wine samples

- Draw a line 1-2 inches from the bottom of the paper using a pencil (pen will not work)

- Mark with an X or dot where you will place the samples.

- Use capillary tubes (one for each sample – don’t mix them up) to draw up a very small sample of the the standards (malic, lactic, and tartaric) and then the wine samples and drop a very small amount of the liquid onto the paper. You will notice it will spread out once it hits the paper so be sure not to drop too much liquid. Less is more here.

- Let the dots dry and repeat 3 times. This will make it easier to read down the road.

- Roll the paper up and staple either side without the paper overlapping onto itself.

- Pour a small amount of paper chromatography solvent solution into the bottom of the plastic jar. Be careful to not inhale this. Place the stapled paper, sample side touching the solution, into the jar. Screw the lid on and let sit for ~8 hours, or enough time for the solvent to reach from the bottom to the top of the paper.

- Take the paper out (carefully) and let it air dry until the entire sheet turns blue and yellow dots are clearly visible.

- Match up where you see specific acid dots with the wine samples and you can detect if malic and/or lactic acid is present in each sample.

Helpful hints

You will likely need to run this test at least a couple of times to see the decline in MLB and confirm its completion

Be sure not to add any potassium metabisulfite to your wine until MLF has completely finished!

Use space heaters or a warm room for wines undergoing MLF to help speed the process along

Collect your test samples

Cold weather fermentation

Brrr… it’s starting to get cold outside! Especially here in New England.

In the Northeast we get the joy of experiencing four distinct seasons. Harvest time is filled with lots of excitement in the air during the warm days and cool nights… but when the warm days start to turn into cool days too, things can get a little more complicated if your wine isn’t done fermenting.

But once the alcoholic fermentation slows down and eventually ends, if the malolactic fermentation (MLF) hasn’t finished and your wine is in a pretty cold (or even cool) location, it can be difficult to get MLF to finish. A half completed MLF can pose some issues in and of itself: delayed SO2 additions, persistent fizz, and stability issues down the road.

So what can you do to ensure you have as smooth a fermentation as possible that isn’t TOO quick, yet doesn’t drag on for too long?

- Choose earlier ripening varieties if you live in cold regions and/or the place you ferment your wine is in a cold place like a basement/cellar.

- Try co-inoculation as your method of malolactic fermentation.

- Use space heaters as needed. These can be placed in small spaces with your barrels to prevent MLF from slowing down or even stopping entirely.

- Choose a fast fermenting yeast strain.

What are the potential results of making wine in cold weather?

- Stuck alcoholic fermentation

- Stuck malolactic fermentation

- Unintentional cold stabilization (this can be positive or negative depending on the wine and style you’re attempting) as it can affect the TA even when you don’t want the TA to move, whether upwards or downwards.

Remember to keep a careful eye on your fermentations as they happen, because you can catch sight of a slow or sluggish fermentation caused by cold weather before it’s too late. Happy fermenting, and remember to keep your aging vessels bundled up and warm enough to keep that fermentation going strong.

Timing your malolactic fermentation

You’ve decided you want your wine to undergo MLF. But when should it happen?

There are a couple different schools of thought on this. You can either add the bacteria so it happens simultaneously with alcoholic fermentation (“co-inoculation”) or after it has completed (“sequential inoculation”).

What’s the purpose of MLF?

The process of converting harsh malic acid into the softer lactic acid is easy to do and can alter the wine significantly. It changes not just the amount and type of acid present, but how the wine is perceived overall. While this conversion can happen on its own without your intervention, it is highly recommended that you inoculate with a chosen malolactic bacteria in order to best ensure everything remains healthy and in balance from start to finish.

Whether you choose to co-inoculate or do it sequentially is completely up to you – both are acceptable! Either way, you just want to be sure that your juice/must is balanced and undergoing (or underwent) a healthy fermentation, to better guarantee the health of the subsequent MLF. The preparation of the malolactic bacteria will be the same regardless of when it gets added. Some require a rehydration period and some can be added directly to the wine. Some are liquid and some are in freeze-dried form. Acti-ML nutrient and Opti-Malo are a helpful additives to use to help the conversion reach completion without any issues. Think of Acti-ML and Opti-Malo as the equilivent of Go-Ferm and Fermaid K, but for malolactic bacteria.

Why should I do co-inoculation?

- MLF generally completes more quickly with this method due to:

- higher temperatures thanks to alcoholic fermentation being underway

- lower alcohol levels at the onset of MLF

- higher nutrient levels

- You won’t need to use an external heat source

- SO2 can be added earlier on in the wine’s life since MLF is completing sooner

Are there any benefits to waiting until after alcoholic fermentation has finished?

- Some believe that ML bacteria and yeasts will be fighting for the same nutrient sources, adding a potential layer of stress

- Ability to focus on one conversion at a time

I’m deciding to wait to add ML bacteria because that’s what I’ve always done.

OK, that’s fine too! If you’re choosing this route, then wait until the Brix has dropped to about 5.

Are there any downsides to waiting to add ML bacteria?

- The wine is unprotected from SO2 for a longer period of time since you can’t add SO2 until MLF is complete.

- You will likely need to use external heat sources to keep the wine warm enough to finish MLF in a timely manner. This means more labor and energy expense.

- Higher alcohol levels can slow the speed of ML conversion or even stop it completely.

Overall, the benefits of co-inoculation seem to outweigh any benefits of the sequential method. Of course, if you have a preference and it works for you, that’s all that matters. As long as your fermentation and ML conversion are happy and healthy, you’re good to go!

What else can I do for a good MLF?

A chosen ML bacteria + proper temperature + good nutrition + not overadding SO2 = a recipe for healthy MLF. Whether you co-inoculate or add toward the end of AF is up to you and your preferences. Regardless of which option you choose, using paper chromatography to track the process is always recommended.

Recent Comments